INTRODUCTION

Sculpture is a medium that can sit on the boundaries of art, craft and design, so we were fascinated when presented with the opportunity to speak with sculptor Patrick Dougherty who has created work internationally. The American artist has made a living devising public works from saplings that he collects local to each site, involving the neighbourhood community where possible in his process.

In two decades he’s created upwards of two hundred large scale sculptures in the public domain, as well as the occasional work for gallery spaces. I was keen to learn his thoughts on the difference in these two arenas, whilst probing further into the background of his life and work. A fascinating individual that we trust will engage and inspire many of you, read on below to see what you think for yourself.

ABOUT PATRICK DOUGHERTY

Born in Oklahoma in 1945, Dougherty was raised in North Carolina. He earned a B.A. in English from the University of North Carolina in 1967 and later returned to the University of North Carolina to study art history and sculpture.

Combining his carpentry skills with his love of nature, Patrick began to learn more about primitive techniques of building and to experiment with tree saplings as construction material. Over the last thirty years, he has built over 230 of these works, and become internationally acclaimed.

Interview date: 28th of December, 2012

1. WHO IS PATRICK DOUGHERTY, AND HOW DOES HE MAKE A LIVING?

I make my living as a sculptor and saplings are my game. I live in Chapel Hill, NC and travel extensively to do my work. In fact, I work for three weeks of each month on location and normally make ten sculptures a year, primarily in the United States, but recently in Melbourne, Australia. As I write this today, I am in Belgrade, Serbia making a plan to build a sculpture in front of the new American embassy here.

I have been working as a full time sculptor since the mid 1980’s and have always received an artist fee plus expenses to build a sculpture on site. My style throws me onto the world’s street corners without studio doors to close, and I enjoy working in a way that reveals the process of building something in an unconventional way. Travel has also meant that I have slept in all the short beds, the hard beds and some of the coldest beds. And my advice to those who are expecting guests is to test that bed in the spare room; it’s likely past its prime.

2. HOW DID YOUR CAREER AS A SCULPTOR BEGIN AND WOULD YOU RECOMMEND THE PATH YOU TOOK TO OTHERS?

Childhood play in the woods of North Carolina was my initial foray into hunting and gathering, and with my brothers and sisters I hollowed out living thickets to make bedrooms, kitchens and more. I was interested in my father’s medical career, and early on, earned an MA in Hospital and Health Administration from the University of Iowa. Even so, I was also my mother’s child, and I responded to her zany artistic temperament and construction knowhow. I often laughed at her peculiar need to reconstruct the furniture in our family home. Ultimately, the pull of the moon became too great, and I enrolled in sculpture and art history classes at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, NC. The day I entered the art lab there has remained the best day of my life. Previously, I didn’t know there were other people like me — like-minded students who loved to work with raw material and see their ideas flower in three dimensions. I was a late bloomer, but nevertheless, I decided to build a studio and get to work.

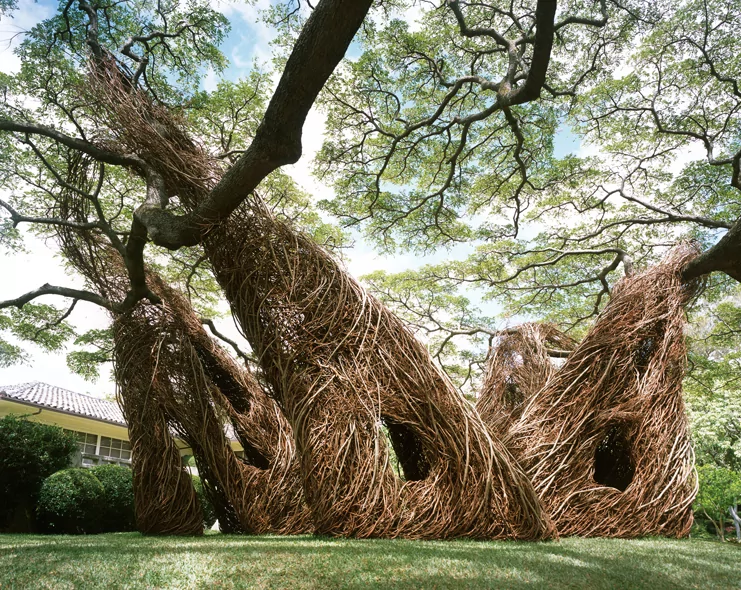

Patrick Dougherty’s 2003 installation, entitled Na Hale ‘O Waiawi, is a complex of bee-hive-like stuctures threaded in and around the magnificent monkeypod tree that graces the grounds at the Contemporay Museum in Honolulu, Hawaii.

3. IN OVER TWO DECADES YOU’VE CREATED UPWARDS OF TWO HUNDRED LARGE SCALE SCULPTURES, SO OUT OF THESE, WHICH DO YOU LOOK BACK AT WITH MOST PRIDE AND WHY IS THIS?

I remember every sculpture as a win and am amazed at the receptiveness and good will of most communities. Building a sculpture on site takes forethought and planning, but the work is actually crafted by facing the problems that arise each day. Not only do the sites and sponsors vary widely; but also often, I am at the mercy of the characteristics of the saplings nearby. For example, this October in Australia, I had too many big sticks and no small branches with which to festoon the surface of the Little Ballroom. A month later I worked at Fresno State University, in California, on the Learning Curve where I had the reverse situation. Perplexed, I shunned my overabundance of smaller rods and fantasized instead about the long flexible ones left back in Melbourne. Whether it is concerns about materials, volunteers or vulnerable underground services, in each of 238 three-week segments, I have engaged in the tenuous process of looking for starting points, gathering material, finding volunteers and meshing my idea with the intended site. During these installations, I wanted a good effect for the public, but my own secret reward has been the thrill of transforming a half-baked concept into a really compelling one despite the many variables. If forced to choose, my last work is always my favorite, at least for a week. It’s inevitable that as I begin to struggle with the opportunities of next month’s site, the luster of my last old favorite fades.

4. PERSONALLY I REALLY ENJOY THE IRONY FOUND IN SOME OF YOUR WORK, WITH VERY ORGANIC AND NATURAL SCENES OF YOUR SCULPTURES OFFSETTING THAT OF THE CONGESTED, NOISY CITY ENVIRONMENT. IS THIS SOMETHING YOU EVER PLAY ON, AND HAS THIS CONTRAST EVER BEEN A MOTIVATION FOR WORK YOU’VE UNDERTAKEN IN THE PAST?

I do find it humorous to have trees over-taken by branches and buildings invaded by trees. I also like the irony of contrasting contemporary architecture with ancient ways of working and providing an idyllic portal in the midst of downtown bustle.

Giving my sculpture a sense of movement, the sweep of a natural phenomenon, and the vitality of a sketch depends on a rough and tumble drawing style. Sticks are the material of bird nests, but also bundles of natural lines with which to draw. Striking a sheet of paper with a pencil often produces a tapered line as the mark starts with one weight and finishes with another. Sticks are naturally tapered; thus, many conventions of drawing can be used to accumulate a rich and textured surface, which seems to sweep along and implies motion and vitality.

5. WHAT WOULD YOU SAY ARE THE PITFALLS AND, MORE IMPORTANTLY, THE BENEFITS OF WORKING IN THE WAY THAT YOU DO?

Beyond the huge personal pleasure I gain from working with the simplest materials in a complex world, I believe that a well-conceived sculpture can enliven and stir the imagination of those who pass. For viewers the pleasure is elemental and beyond politics and financial forces. I like activating public spaces and being part of the world of ideas.

6. WHERE DO YOU STAND ON CREATIVITY AND EDUCATION? AS A SCULPTOR YOURSELF I’D IMAGINE YOU’D ENCOURAGE THE IDEA OF THE TWO COMBINING MORE?

I think of creativity as the ability to problem solve fluidly and to produce a positive outcome. It also means thinking on the verge and feeling a sense of imminent possibility as you seek a solution. I try to approach a new site, a new situation, expansively, unencumbered by predisposition. When I have the opportunity to have a group of students come by, I always encourage them to make things, because grappling with materials produces new ideas.

7. WE ARE OBVIOUSLY BIG FANS OF YOUR WORK BUT THERE’S ALWAYS INDIVIDUALS THAT CAN NEVER SEEM TO GRASP THE VALUE OF ART, SO WHERE FOR YOU LIES THE REAL VALUE IN WHAT YOU CREATE AND HOW DO YOU COMBAT SUCH OPINIONS IN YOUR OWN MIND?

The value of working on a project in public for three weeks is the chance for the viewers to see the sculpture develop over time and participate in the process. When someone calls the police on the first day about a culprit unloading limbs across from their house, often it is the same people inviting me for dinner before the opening celebration. The building process is a transformative one where saplings are woven into a storyline and convey a credible illusion. I believe a good sculpture should provide the viewer with many starting points and promote associative thinking. For example, a successful sculpture might induce dreams of simple shelter, memories of childhood play or pleasant recall of an early tryst shielded by a favorite tree. I often hear, “I don’t like art, but I like this” and in this statement I imagine that “sculpture” has wormed its way a little closer to everyday life.

8. IS THERE A BIG DIFFERENCE IN WORK THAT IS CREATED AS PUBLIC INSTALLATION AND PROJECTS HIGHLIGHTED IN A GALLERY SPACE? DO YOU FEEL THESE APPEAL TO A DIFFERENT DEMOGRAPHIC FOR EXAMPLE?

Galleries are generally neutral spaces where ideas are presented without competition. For example, an abstract work conceived in a studio can be appreciated fully for the its size, style and message, yet move the same work onto the street and it is lost among parking meters, light posts, cars and other well-designed objects around it. A work conceived for a park or streetscape must have an appropriate scale and must resonate subliminally with its surroundings. Its placement requires consideration of traffic patterns and quirks of human behavior. Viewer safety, weather conditions and public wear and tear are all important considerations. Basically I have to strategize to reduce impediments to viewing and to develop interplay with the site that encourages engagement. But whether it is a gallery that provides a neutral forum or a busy street corner that must be accommodated, the artwork itself has to contain the energy to connect viscerally with those who view it.

9. WHEN YOU CREATE A PROJECT I’D IMAGINE YOU DO SO BECAUSE YOU’VE BEEN ASKED OR COMMISSIONED. WHICH MAKES ME A LITTLE CURIOUS TO YOUR OPINION ON WORK OF ARTISTS THAT CREATE PUBLIC ART WITHOUT PERMISSION, DO YOU THINK THIS WORK HAS A PLACE?

I think all cutting edge work has its guerrilla phases and, if it proves relevant, it matures and is sanctified. I had my own acting-out-in-public phase and I know others who started out without permission. Artists should persist and present their ideas. Sometimes their disregard for convention or the law puts them in jeopardy and only time can tell if “bad behavior” is a worthy effort. In some more repressive countries it can translate into jail time or house arrest for the artist. I personally do not like tagging with its sense of juvenile anarchy and am hoping that it will become irrelevant soon.

10. ALTHOUGH YOU ALWAYS LEAD EACH PROJECT YOU UNDERTAKE YOU OFTEN INVOLVE VOLUNTEERS FROM THE LOCAL COMMUNITY WITHIN YOUR WORK. HOW DOES THEIR INCLUSION IMPACT UPON THE FINAL DESIGN OF A SCULPTURE, AND IS IT A CHALLENGE TO GET EVERYONE WORKING TOGETHER UNDER ONE SCHOOL OF THOUGHT?

Early on, I learned to partner with organizations and invariably we would seek volunteers to help gather large quantities of saplings. I am not the only person out there who likes a good sapling; closet stick collectors started coming out of the woodwork and before long I had volunteers of every ilk looking for a chance to indulge their basic building urges. Because of that extra energy and good will, I have been able to make larger works and it is also clear that it’s harder to hate a sculpture if one of your neighbors has worked on it.

In the starting phase, I set up the parameters of the work, laying out the footprint and projecting how the final product should feel in its site. I sometimes make a drawing or small model so that everyone can see the idea. I break the process of building into smaller pieces, so that a volunteer can practice without fear of failure. Those who return several times tend to have more complicated tasks. I try to do the work on the entire exterior myself because those sticks are the most crucial to the finished look. The interior demands lots of hands and enormous detailing and much of the assistance is applied within.

I am energized by the hubbub of the communal work, but I remain fully responsible for the outcome. It is my work and the volunteers are free to relax and just dig in. It might be a hippie and a businessman working with a grandmother and a high school senior, and for a short period of time, we, like a small indigenous band, work furiously on beauty and burnish our object until it shines in its location.

11. AS FAR AS I’M AWARE YOU’VE ONLY EVER BUILT SCULPTURES IN ONE MATERIAL, HAVE YOU EVER BEEN INTERESTED IN EXPERIMENTING WITH ANOTHER OR PERHAPS COMBINING A FEW TO CREATE THE SAME DESIRED EFFECT.

When I am at home or working with friends any material is fair game. But in my public work, I still enjoy finding something new while holding the material constant. Each time I say, “What unique opportunities do I have in this situation that I will never have again?” Experimenting is a necessity but a career is built on focus and wringing huge potential from limited territory.

12. WOULD YOU SAY WORKING AS AN ARTIST LACKS FINANCIAL SECURITY? IF SO, WHAT WOULD YOUR ADVICE BE TO YOUNG ARTISTS CONSIDERING WORKING ON THEIR OWN PROJECTS FULL TIME?

An artist has to make the work pay, or he or she cannot afford to continue in a serious full time way. One of the keys to success is producing a lot of work and developing a momentum. It is also important to gain credibility and have people “who are supposed to know” testify about your work. An artist has to enter exhibitions, apply for grants and opportunities and keep the burner hot. I believe that if an artist works on his or her own behalf, half as hard as they are willing to work for others, they will see the stumbling blocks start to crumble. I have always made a living from my work, in part because I am willing to travel away from home in order to gain commissions and to exert myself seriously to make those opportunities work out.

13. WHAT ARTWORKS DO YOU FIND EMPOWERING, AND WHOSE CREATIONS HAVE MADE YOU RETHINK HOW YOU UNDERTAKE WORK?

Robert Smithson was an early inspiration because he broke the mold and took work into the landscape and out of commercial play. And I had my moment with Ana Mendieta when I saw a picture in Time Magazine of her body painted like tree bark appearing indistinguishable from a tree. I took heart from seeing David Smith’s drawings in the Hirschhorn and realizing mine were in fact okay, and I had a humorous moment in James Surls’ studio in Colorado when a student assumed he had a factory for art and asked where all his art workers were. He stood with a hand ax in front of a half finished mound of work and said “Darling, sculptors sculpt.” I really am a pushover for all sculpture, professionals and part-timers alike. I look for the intent and try to figure how they solved their problems.

14. HOW DO YOU CONTINUE TO GROW AND DEVELOP AS AN ARTIST? WITH THIS IN MIND, WHAT ADVICE DO YOU HAVE FOR OUR READERS?

Becoming a hack is the nightmare of all professionals. For me making sculpture is a source of renewable energy. It means making something provocative and eye-catching in each new community. It means reaching out and opening oneself to new possibilities. It means doing your best and working just a little over capacity. I think of it as a chance to participate in the largest conversation.

If your readers don’t already tinker, I hope they will grab a bit of the material world and make a fanciful object or something they need. Such activity has helped me to personalize my world and has provided a gleaming portal to an enhanced life.

Post a comment