Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook Interview

Introduction

When I came across American architect Naomi Pollock‘s new book on Japanese Design I knew I had to reach out and see if we could put together something for the blog that might inspire.

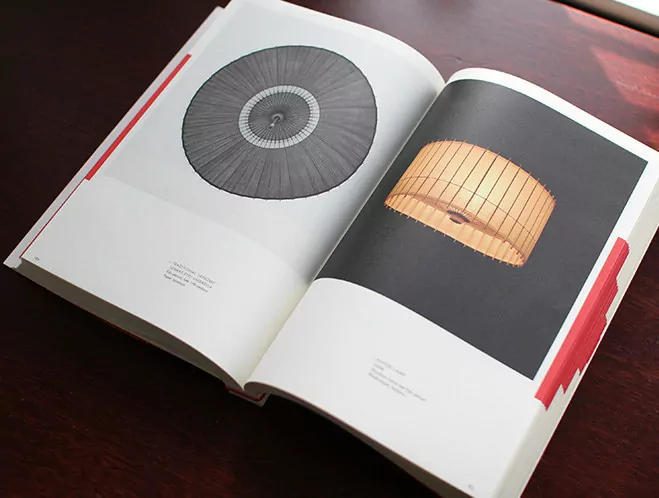

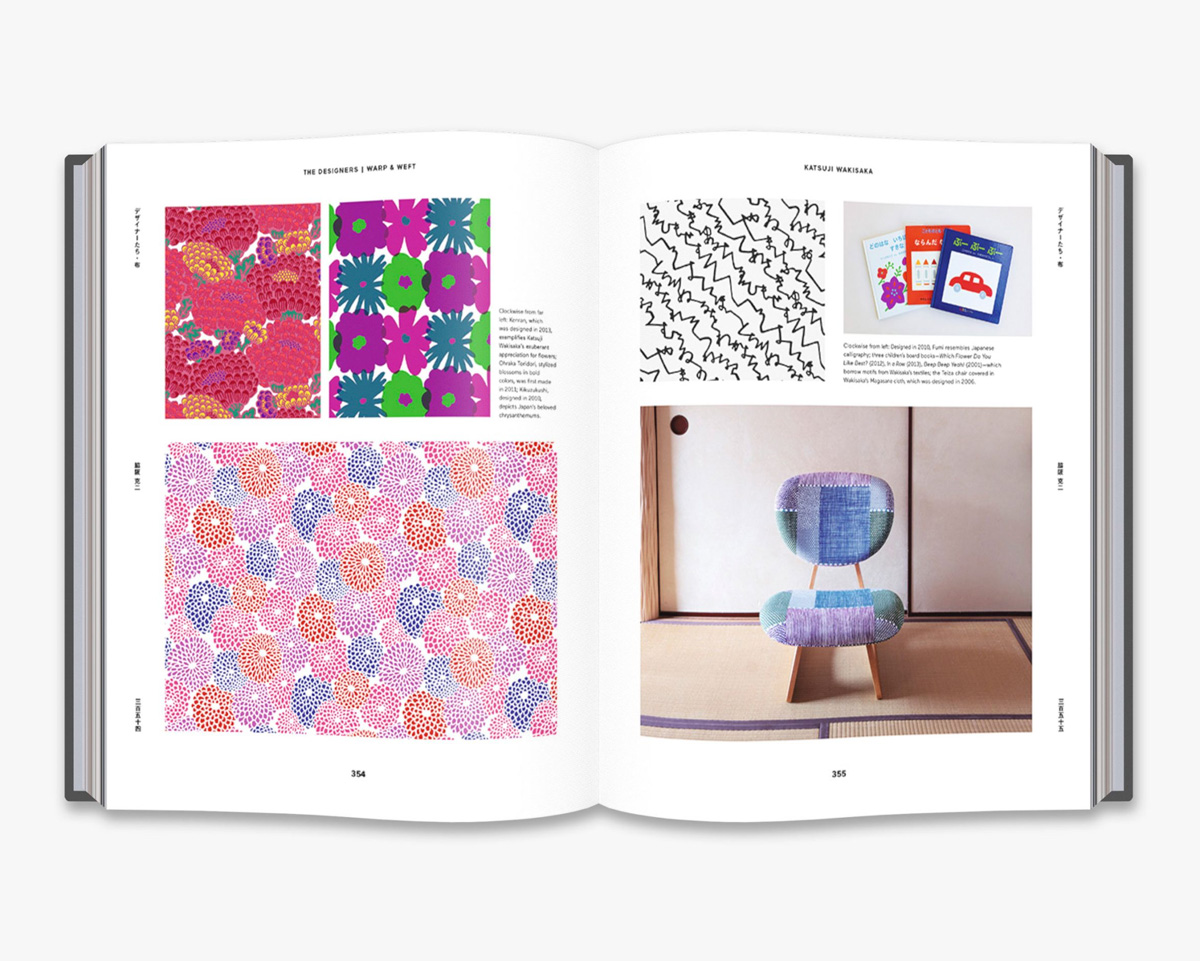

Naomi’s new book ‘Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook’ is very impressive, offering a complete overview of Japanese design to date. Inside profiles more than 70 creators, based on the author’s interviews with designers, their colleagues and family members, as well as leading curators and critics. Featuring hundreds of objects inside, this volume will no doubt become the definitive work on this specific subject for many years to come.

I think it’s vital to see the progression in design, and this book also shows us the importance of craft in Japanese culture and the part it has played in the evolution of Japanese design. I hope you will enjoy my interview with Naomi below and also go on over and support here book by purchasing it here.

Instagram: @sweathesmallstuff

Website: naomipollock.net

Interview

1. Hey Naomi! Would you be as so kind to introduce yourself to our readers?

Hello! I am an American architect and author who writes about architecture and design in Japan mainly. My work has appeared in a variety of publications including, Wallpaper*, Kinfolk, Dwell, The Financial Times, and Architectural Record for whom I am the Special International Correspondent. In addition, I am the author of 8 books, such as ‘Modern Japanese House’, ‘Made in Japan: 100 New Products’, ‘Juataku: Japanese Houses’, ‘Sou Fujimoto’, as well as my new book, ‘Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook.’ Please also check out my instagram feed, sweathesmallstuff.

2. You’ve been covering Japanese architecture and design for more than 20 years now. Why do you feel such a strong connection to Japanese design in-particular? Why were you initially drawn to it and why does it continue to be of interest?

I first came to Japan on a scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education enabling me to get a second master’s degree under the guidance of Prof Hiroshi Hara, one of the only practicing architects at Tokyo University at that time. During my first meeting with Prof Hara, he asked me what I wanted to study. I knew very little about Japanese architecture but I knew for sure that the architectural culture of Japan looked very different from that of New York where I had been working on the design of big buildings at a big Manhattan firm. So I simply responded that I wanted to understand why buildings in Tokyo looked so strange. Instead of consistent street walls, organizing urban elements and any kind of common architectural language, the city’s buildings were an enormous hodgepodge. Prof Hara immediately responded that in order to understand the contemporary, I had to understand the old. Consequently, I wrote my master’s thesis about minka farmhouses which enabled me to take a close look at the history of houses in Japan. Happily, Japan has this wonderful custom of kengakukai, or open houses, when architects can invite everyone they know to view their new work before it is given over to the client. Attending as many of these events as possible became my own private curriculum and enabled me to build my knowledge of new buildings. This growing knowledge base led to the launch of my writing career and once that was off and running I opened my eyes to design at various scales. Where design is concerned, there is so much that Japan does well. One important theme in my new book is how Japan’s craft legacy continues to inform its design culture at multiple scales, even the mass-produced and the machine-made.

En soy sauce cruet, Masatoshi Sakaegi (designer), 2000. Photo credit: Ryo Fukaya, Studio Essa

3. Your new book ‘Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook’ is quite extensive in its exploration of Japanese design. How does this compare to some of the other books you have written in the past?

I have had my eye on Japanese design since the 1990s when I was a guest curator of a two-part exhibit for the Art Institute of Chicago. The first half featured new public buildings in Japan and the second half focussed on a selection of products which had been given Good Design Awards by the Japanese government. My new book is my most extensive exploration of Japanese design to date. Over the years, it became increasingly apparent to me that there was a need for an up to date book about the development of Japanese design. Especially as the popularity of Japanese goods proliferates worldwide. People buy Japanese products but know so little about them — who made them and why. This book aims to fill in some of those gaps.

4. I enjoyed your introduction in the book analysing “The Craft of Japanese Design”. I think it’s difficult for someone outside of Japan to realise how important craft is to the Japanese and how closely connected their culture is. You touched on ‘monozukuri’ in your introduction. Could you tell us a little more about this meaning and the philosophy behind this word?

Monozukuri is a compound word which simply means “making things.” But it is imbued with a much deeper meaning. It is as much a mindset as a mode of working. As I stated in my book ‘Made in Japan: 100 New Products,’ it is “the heartfelt commitment by the person wielding the chisel or operating the die cutter to do his or her best. This drives the maker to refine, study with the eye and the hand, and refine again, no matter how infinitesimal the change.” This intensity and focus is evident everywhere in Japan, from the traditional ceramist to the factory worker at a paper box company to the person flipping sticks of grilled chicken at the local yakitori bar.

5. Craftsmanship in Japan has always been used as category to help people in their daily lives. This very much contrasts to the Western ideology of adornment or making work for decorative purposes. Where do you think this derives from and why do you think mastering a craft is so important to the Japanese?

In Japan, there is so much pride taken in the making of things. The meaning of craft in Japan is much deeper in some ways. It is not about an aesthetic but rather the underlying philosophy.

Tetu (iron kettle), Makoto Koizumi (designer), 2013. Photo credit: Yosuke Otomo

6. In the West we have lost many of the small factories and workshops that used the skill of people in the making process. Japan still has a healthy amount that are continuing to be supported. You even find designers such as Oji Masanori or Rina Ono who are collaborating with these companies to keep their work relevant for the modern age. Why do you think Japanese designers are so willing to work with such factories?

These collaborations between young designers and aging factories yield wonderful opportunities on both sides. For young designers, they can be chances to realize their own work and to get to know the manufacturing process very intimately. This in turn informs their designs and design process. Many young designers are committed to helping these factories stay afloat. They see great potential in their highly developed technologies and want to find new, relevent applications for them. Most young designers who choose to go this route have a deep appreciation for the history of these small factories and want to see them survive.

7. As well as covering the classic design of Japan you also decided to highlight packaging, food, and other niche industries. Why was it important for you to look in to these particular areas of design?

Part of my point is that design is everywhere in Japan. It is not limited to high end household products. On the contrary, everyone in Japan encounters design excellence in the subway stations, convenience stores and on the street. Many times people don’t even realize how brilliant some of these designs truly are, such as the wrapper for the onigiri rice ball which carefully separates the seaweed from the rice. This keeps the seaweed crunchy until it is ready to be eaten. The subway manner posters are another example. They are intended as reminders of how to behave and not to behave on the trains. Each one is authored by a graphic designer who rotates annually.

Spoke Chair, Katsuhei Toyoguchi (designer), 1963. Photo credit: Tendo Co., Ltd.

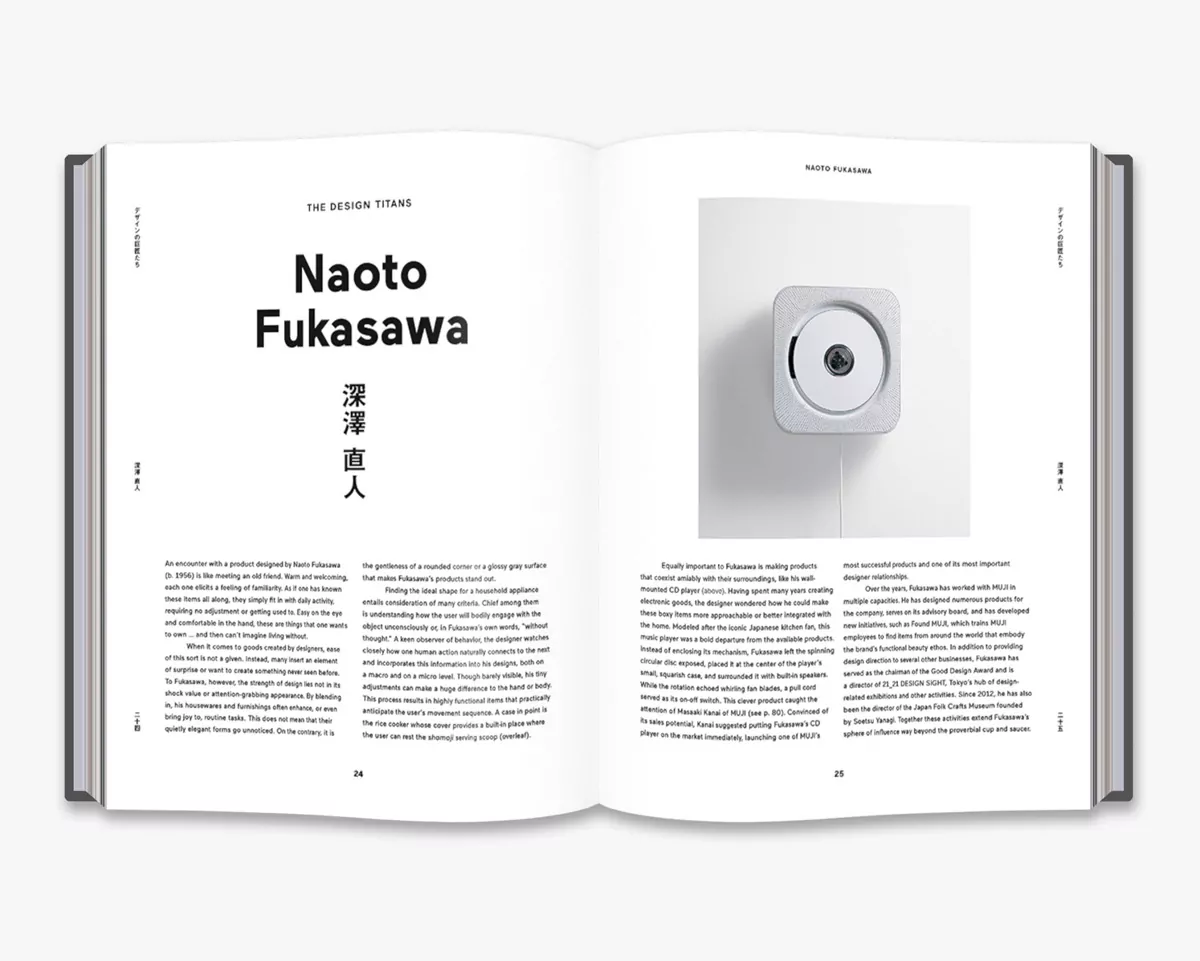

8. I love that with this book you tried to highlight current designers who are working on innovative projects. Which designer stood out to you personally? Was there a particular piece of design that really sparked your imagination?

This is a really tough question. It is like asking me to choose my favorite child! One product which really turned my head and is partly responsible for my writing this book is the Spoke Chair designed by Katsuhei Toyoguchi in the early 1960s. While its spindled back nods politely to the classic Windsor Chair, its broad, oval seat enables the user to sit agura style (or cross-legged) and is set at such a height that the user can be at eye level with others seated on the traditional tatami mat floor as well as on Western chairs. Truly remarkable. Plus it is an extremely beautiful object. It is still produced by Tendo Co Ltd in Yamagata Prefecture.

9. Thinking about MUJI and their strong focus on stripping back what’s not necessary, how do you think Japanese design might flow in to our own Western way of thinking?

The MUJI ethos of “this will do” (in the words of Naoto Fukasawa), has broad appeal that goes way beyond Japan. So many MUJI products simply meld effortlessly with daily life, no matter where one is living. They perform well and hold up over time. What’s not to love?

10. As we transition to digital living, which is no doubt being fast forwarded with the current pandemic, can you see any future design patterns? Where do you think we will go from here?

There is a tendency these days to make objects increasingly smaller or even disappear altogether, especially in the area of electronics. In Japan, some people feel that there is a shift away from designing physical objects towards the design of experiences. But no matter what happens, there will always be a need and desire for beautiful dishes and comfortable sofas. And I will be there to report on them!

Click here to purchase Naomi’s new book ‘Japanese Design Since 1945: A Complete Sourcebook’ ⟶

Lucano ladder, Chiaki Murata (designer), 2009. Photo credit: Manabu Sato